library(tidyverse)── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

✔ ggplot2 3.5.1 ✔ tibble 3.2.1

✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

✔ purrr 1.0.2

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorslibrary(janitor)

Attaching package: 'janitor'

The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

chisq.test, fisher.testlibrary(infer)

library(openintro)Loading required package: airports

Loading required package: cherryblossom

Loading required package: usdatalibrary(mosaic)Registered S3 method overwritten by 'mosaic':

method from

fortify.SpatialPolygonsDataFrame ggplot2

The 'mosaic' package masks several functions from core packages in order to add

additional features. The original behavior of these functions should not be affected by this.

Attaching package: 'mosaic'

The following object is masked from 'package:Matrix':

mean

The following object is masked from 'package:openintro':

dotPlot

The following objects are masked from 'package:infer':

prop_test, t_test

The following objects are masked from 'package:dplyr':

count, do, tally

The following object is masked from 'package:purrr':

cross

The following object is masked from 'package:ggplot2':

stat

The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

binom.test, cor, cor.test, cov, fivenum, IQR, median, prop.test,

quantile, sd, t.test, var

The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

max, mean, min, prod, range, sample, sum

15.10.5 Comment on the effect size and the practical significance of the result.

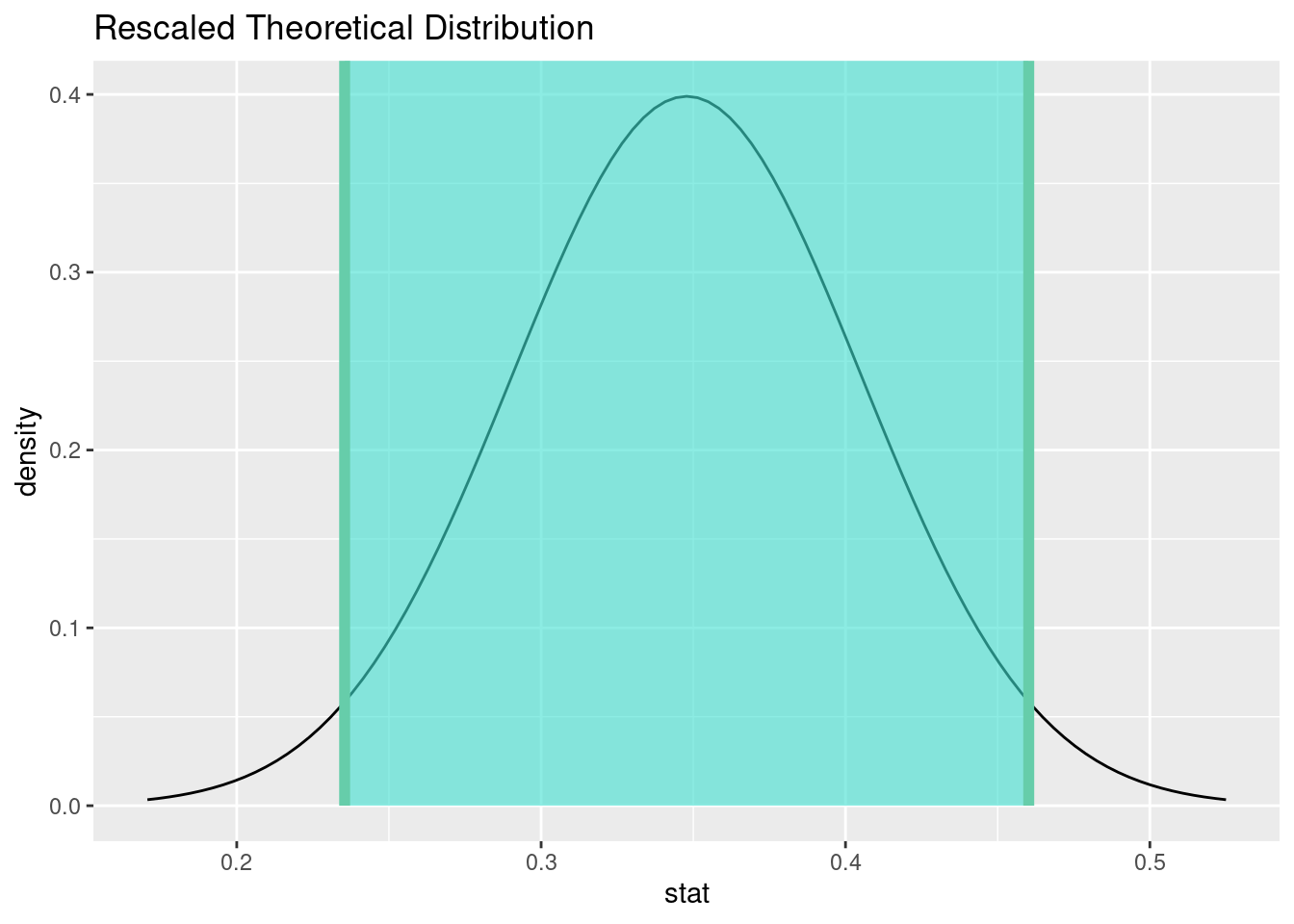

We estimate that between 24% and 46% of patients who received heart transplants survived. Even the most optimistic estimate is still below the null value of 50%. This is a significant difference and tells us that it’s not even close to a “coin flip.” Although we are told that survival rates are better when receiving a heart transplant versus not receiving one, there is a substantial risk of death, even with a heart transplant.

Commentary: up to this point in the course, we had scenarios in which we had run hypothesis tests but not confidence intervals, or confidence intervals but not hypothesis tests. This is the first time we’ve run both, so we are now in a position to opine about effect size. The idea is to compare the range of values from the confidence interval to the null value. What is the worst-case scenario? What is the best-case scenario? In either event, is the magnitude of the difference clinically important to these patients? A 1% difference might not be, but a 10% difference might be.

It’s not enough just to reject the null hypothesis and calculate a confidence interval. We want to indicate whether the data makes a strong case about the research question. A statistically discernible result alone (a P-value less than 0.05) will tell us only that we can confidently reject the null. But that cannot tell us if the result in meaningful in a real-world setting.